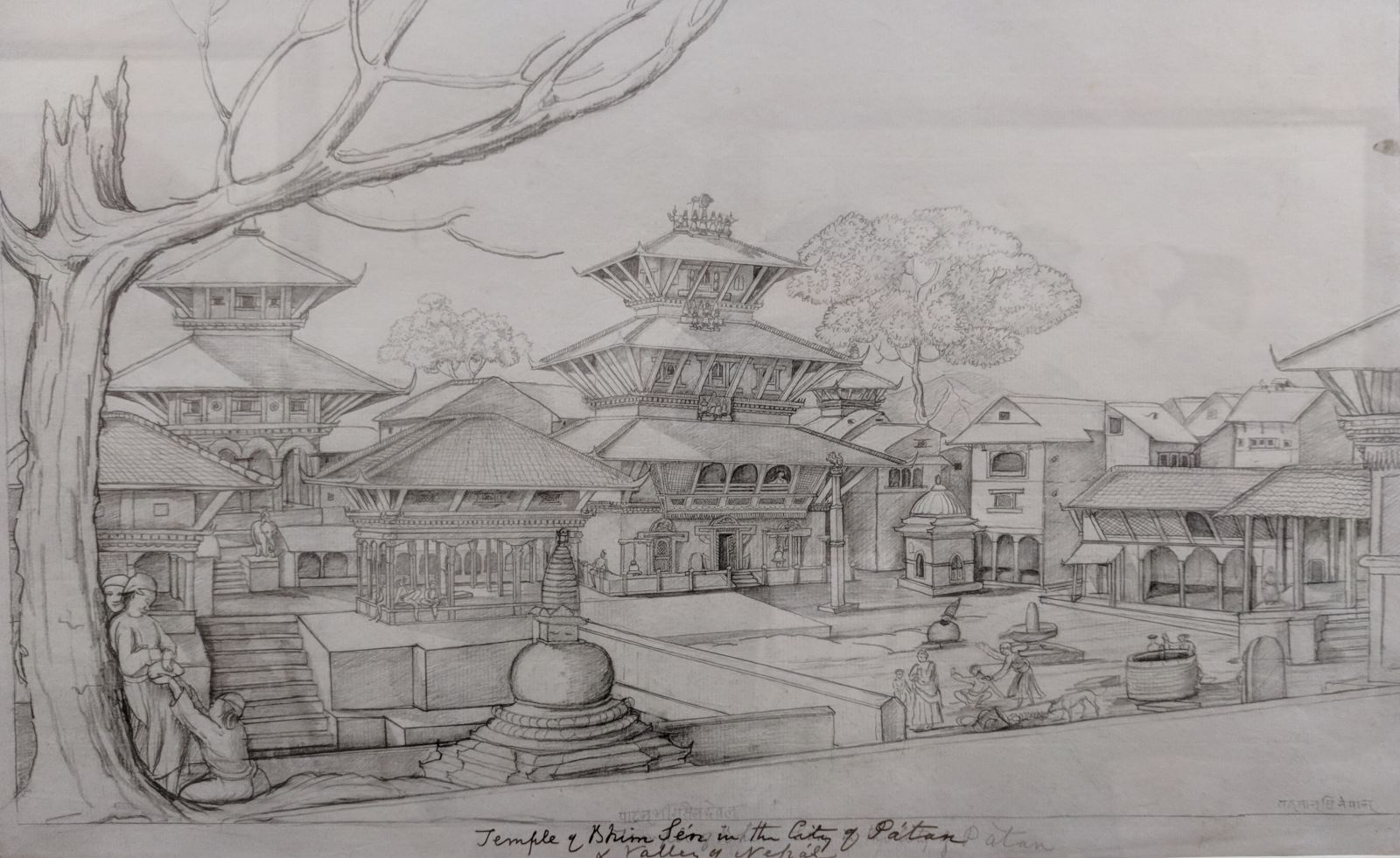

The first sketch of Kubeshwor temple (1840s), Patan, Rajaman Singh Chitrakar. Built in the 14th century (around 1392) by King Jayasthiti Malla. Right next to Kubeshwor is the famous Banglamukhi temple. (pic credit- Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland)

In a land filled with jaw dropping natural beauty, it’s a paradox that landscape and realism art forms never developed in the country until the 19th century. Why didn’t our artists and their patrons ever think of painting the breathtaking nature right before their eyes, or even the grand architecture of palaces and temples? Were they so blinded by religion and perfecting the art of painting deities that all else was not considered important to put on canvas? In neighbouring China, landscape art developed as early as 10th century with ink paintings of spectacular mountains, but somehow its influences didn’t trickle down to Nepal. Why wasn’t much effort put into depicting landscape when Nepal is indeed a visually striking country? A question that art aficionados can ponder upon till dawn.

The era of landscape painting and realism in Nepal ensued only after the Anglo-Nepal war and the Treaty of Sugauli in 1816. After having Nepal cede one-third of its territory, the colonial British Empire appointed an emissary, Brian Hodgson, who served for over 20 years (1820-1843) and did the first systematic study of Nepal’s flora, fauna, culture and languages. Hodgson trained a traditional artist Rajman Singh Chitrakar who can be credited as Nepal’s first ever landscape and realism artist. A decade later, in the 1850s, British doctor Henry Ambrose Oldfield and his wife also painted some brilliant portrayals of Kathmandu Valley. Thanks to Rajman and Oldfield, we have a series of paintings of how Kathmandu looked like in the 19th century.

Rajman was trained in traditional paubha and under the tutelage of Hodgson, grew as a landscape realism artist as well. He painted Kathmandu’s monuments amidst its landscapes and natural subjects like birds, mammals, and people from various ethnic groups. He was the first to give light and perspective to paintings in Nepal as done in realism art, and is credited for the appearance of three-dimensional effects in Nepali painting.

Art historian Sanyukta Shrestha’s research says that apart from incorporating western art influence, Rajman’s work showed distinctive features of Nepal’s people and places. Being a local he understood the environment better than his western counterpart Oldfield whose sketches show general architecture and landscapes. The first pictures of Nepali ethnic groups and their houses can be credited to Rajman’s sketches, according to Shrestha.

This less known name of our country’s art history was given national recognition only in 2012 when the government honored him with two commemorative postal stamps. The tragedy is that Nepal does not own any paintings by this pioneer artist. All of his art collections are in museums abroad, mostly at the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

Another remarkable feature that Shrestha credits Rajman with is his versatility. How an established Nepali artist so easily adopted realism from the West is something that we barely give thought to. While a Nepali artist easily learned western approaches to art, the British did not bother to learn our traditional art. Perhaps, it had to do with a colonial mind set then. Nevertheless, Rajman Chitrakar was well acknowledged in the West, as his sketches were used as references for comparative research on architecture of the subcontinent.

First sketch of Bhimsen temple, (1840s) Patan by Rajman Singh Chitrakar. Dedicated to Bheem, the Pandav brother who is also worshipped as god of business and trade. Built in 1680 by King Srinivasa Malla.

(pic credit – Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland)

In tracing the influence of realism in Nepali art, we next see Bhaju Man Chitrakar who Jung Bahadur Rana took along in his visit to the UK in 1850. Artistic needs then were mainly met to decorate the palaces of the Rana aristocrats with portraits, hunting scenes and decorative paintings. The Chitrakars were the chief palace artists who learned the western paradigms in art to fulfill the colonial obsession of their Rana patrons. In the early 1900s, under Rana patronage, Chandra Man Maskay and Tej Bahadur Chitrakar were sent to the Bengal School of Art in Calcutta, after which they brought a turning point in the development of contemporary art in Nepal. They painted traditional subjects in modern European style. Moreover, Tej Bahadur taught art in Durbar High School and guided a new generation of contemporary realism artists. His students included the likes of Manohar Man Pun, Amir B Chitrakar, Gautam Ratna Tuladhar, D.B Chitrakar, Kulman Singh Bhandari and others.

Early natural realism water color of Tej Bahadur Chitrakar circa 1940s (personal family collection)

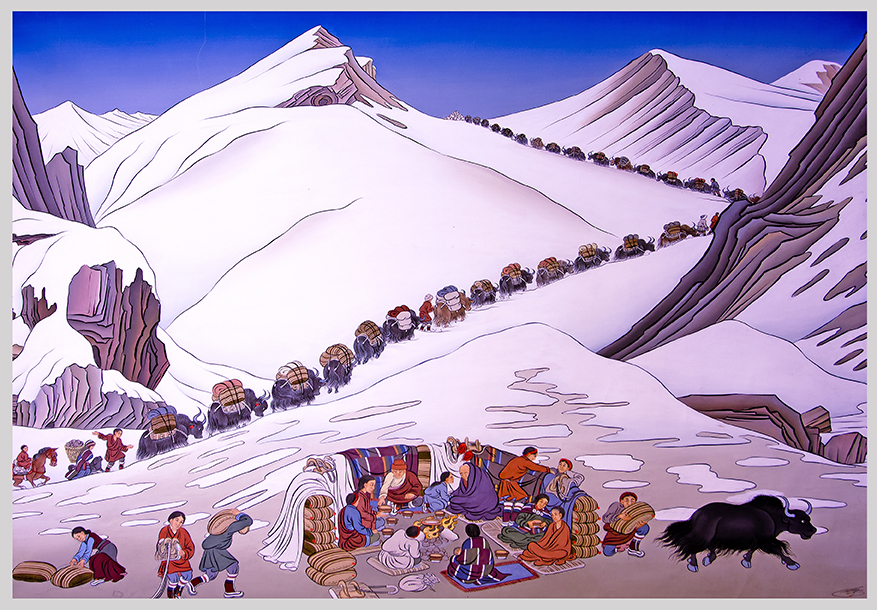

Caravan by Tenzin Norbu (artist's collection) semi-realism landscape, a style developed by the artist

After years of external influence, Nepal’s landscape realism today has developed its own style. We have progressed in this genre with an integration of thangka with realism, brought about by an artist from Dolpo, Tenzin Norbu followed by his student Tsering Samdup. Norbu’s works have appeared in National Geographic magazine, the Academy Award–nominated feature film Caravan and some children’s books.

Norbu experimented with proportion and realism in landscape art, merging it with thangka motifs. He brings a new flavor by placing stylistic thangka landscape forms in the backdrop of realistic Himalayan settings giving motion and energy to the art. He is followed by his student Samdup who experiments further by bringing subjects of contemporary affairs into neo-thangka landscapes.

The two traditional schools of Thangka – Mendi with deep traditional colors and Karma Gadri with harmonious colors – is used in the neo-traditional form of the two artists. The Karma Gadri style is more prominent as it efficiently uses the contrast between a pastel-coloured luminescent background and the main subject in rich strong colors.

Norbu’s and Samdup’s paintings of pristine Himalayan regions are inspired by simple village life with mountainous landscapes, traditional structures, yaks, people, and some issue-based art on how modernity is affecting tradition. In their compositions, they use naturalist methods in landscape with religious images, motifs, people and animals. However, they don’t portray subjects in their actual, realistic form; rather, its captured in an imaginative manner; almost as if combining mythology and reality within a composition – a unique style seen in Nepali landscape realism.

Norbu’s painting entitled ‘Caravan’ depicts the breathtaking landscapes of Dolpo in bright hues. The harsh life of the mountains is concealed by a comic like portrayal to convey an enchanting depiction of the salt caravan life. A bright blue background with yaks and mountains painted semi-realistically a combination that gives a surreal aura of part reality and part fiction.

Samdup’s painting entitled ‘Development’ is heart-rending, showing a present-day scene from the Himalayan regions. An excavator paves the road through a stupa, the yaks attain freedom from centuries of drudgery and float in heavenly clouds; a man on a horseback silently rides away looking back at what once was – all captured in traditional and modern fusion. This combination is what characterizes Nepali landscape realism – portraying a society caught between the old and new and reflecting it in evolving art forms.

.jpg)

The Development by Tsering Samdup (private collection) neo-thanka realism portraying mountain life issues

Realism started in Nepal under the tutelage of a British emissary and then advanced with graduates from the Bengal School of Art. The form has finally come around to having its own distinctive trait in Nepal. This home grown development has not been analyzed much, but a country with an art history of 2000 plus years will naturally imbibe external influences and blend it into its own indigenous techniques to create a distinctive style. Herein lays the value of Nepali realism, a form that portrays our topographic beauty in a unique blend of internal and external schools of art.

References:

- Sanyukta Shrestha, Fragments of Nepali History in the UK

- Susan Vander Heide, Traditional Art in Upheaval: Development of Modern Contemporary art in Nepal

- Lisa Choegyal, Nepal’s history through Art, Nepali Times; December 2020

- Interview with Tsering Samdup