Follow Reudi Frank in his incredible journey as he traverses from Europe to Asia

His eyes still remain electric blue but his blonde hair has an abundance of white now. Ruedi Frank sits across the table from me and says, “You know, for Swiss people, Nepal isn’t all that different.” His enthusiasm, as he gives me the account of the years gone by, is the same as that of the blue-eyed Swiss boy he once was in the 70s, who climbed peaks for fun.

Ruedi was a mountain guide in Switzerland at a very young age and on an opportune day, when attending his English language course in Zurich, he met a friend who was working on a suspension bridge project in a distant place called Nepal.

What is about to follow is told through the eyes of Ruedi, now a banking consultant based in Zurich. Ruedi has been to Nepal fifteen times and brings tour groups to take them on a rather unique tour across Kathmandu and Pokhara. The group has also traversed through Honduras, Guatemala and Mt. Kilimanjaro in Africa. But his aptly named tour group, Frank Adventure isn’t an organized trek; Frank rather stresses on taking people on adventures to seldom mentioned spots and locations like the one he took to Nepal in 1974.

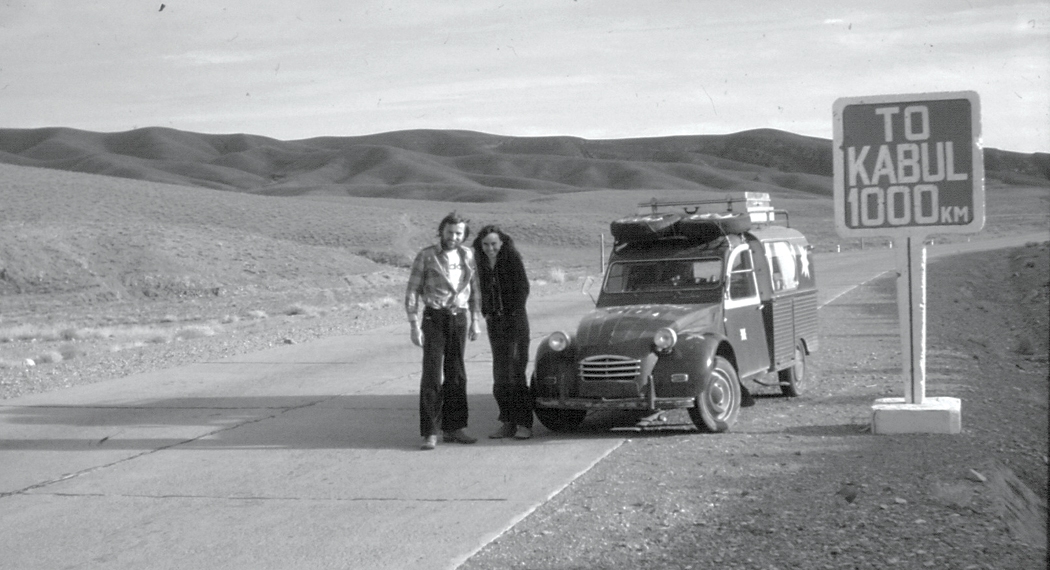

I have this brilliant idea,” the young Ruedi said to his wife, “Let’s take an adventure across Europe and Asia in our car!” So, they packed up in their little Citreon and decided to take this road trip through countries and roads and visas. The year is 1974 going into 1975 and thus begins one of the best adventure stories told as he quickly scribbles in his notebook his travel plan:

Italy –Yugoslavia – Greece – Turkey – Iran – Afghanistan – Pakistan – India – Nepal

It's like a city, but it’s a village isn’t it?”he murmurs. The year is 1975, and the roads of Kathmandu are devoid of traffic. The Basantapur square is filled with foreigners and girls with flowers in their hair. He enquires about lodging and is astounded at the very economical rates. “Brilliant!” he says to himself

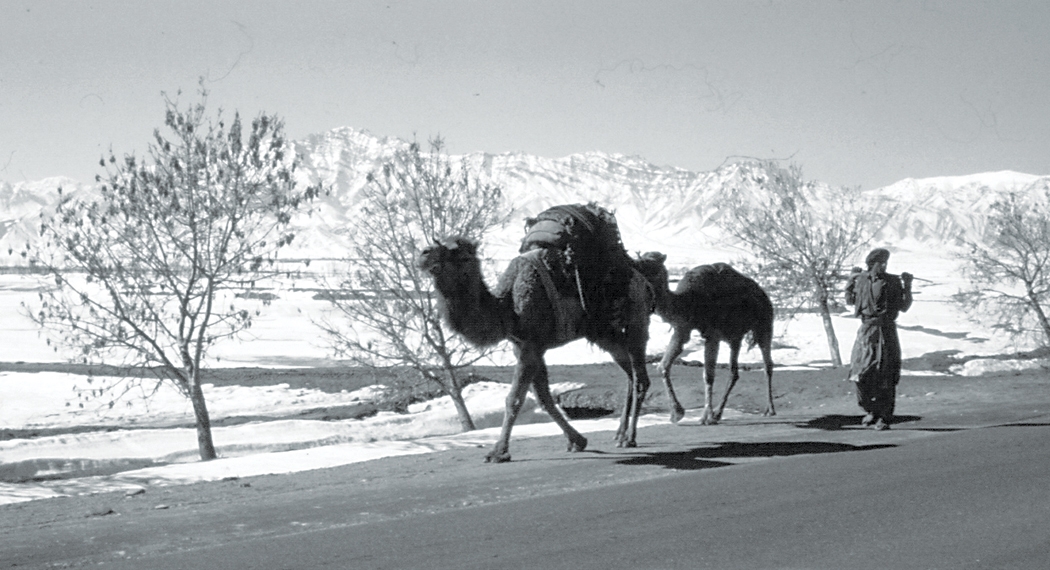

He checks his map and knows he is heading in the right direction. As they make their way into the splendor of Iran, the couple is mesmerized by the magnanimity of the people there, a far cry from what Iran would become some 40 years later. “The Shah of Iran,” he says to himself, “has done well with his country.” The roads turn rockier and the hills get bigger as big men with beards, turbans and pathani kurtas stand on guard outside the cities.

“Ah! Of course, Afghanistan.”

One of these strapping tall blokes beckons them to stop and asks them where they are coming from and where they are heading. “We’re going to Nepal actually,” Franks says very matter-of-factly. At first, the Pathan looks perplexed.

“Oh Nepal! Freak Street!” he exclaims after a considered pause.

“Yes!” young Ruedi nods, smiling.

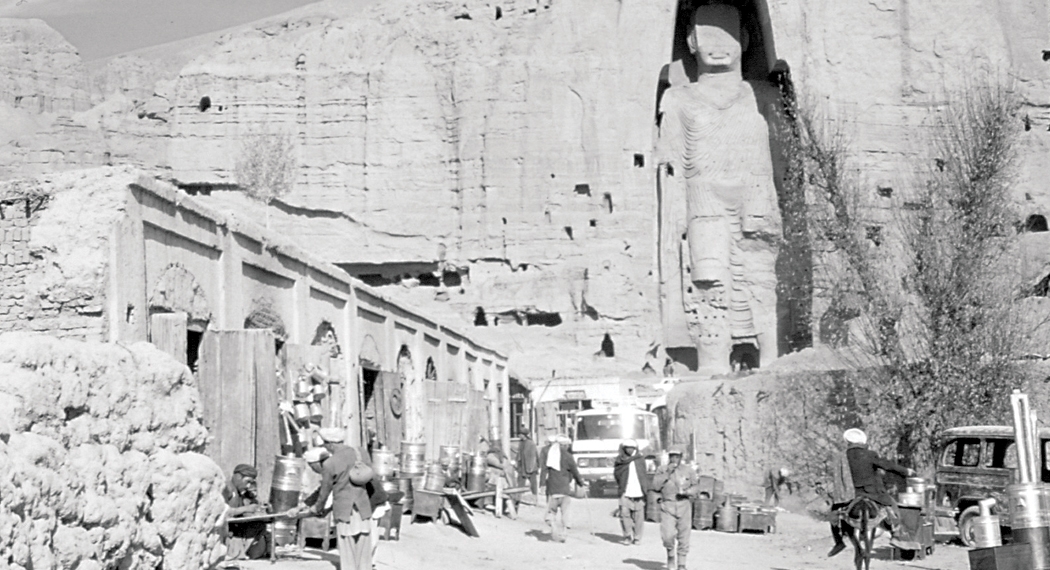

They are allowed to pass and the couple revels in the infamy of Jhochhen, a place still distant from the mountainous terrain they are in right now but all too familiar to where they are actually headed. They make their way across the Pashtun area famous for not being the most hospitable area. They click pictures in front of one of the biggest statues of Buddha in Bamiyam, Afghanistan, nearly 2000 year old. Such grandeur would then lead them down to Pakistan where they are asked for a visa for the very first time in all of their travelling so far.

Sipping tea from his cup at Dwarika’s Hotel, Ruedi reflects on his trip to Nepal and how much time has changed everything. “What a sad predicament,” he laments, “those statues were destroyed; blown up by the Taliban in 2001. It’s such a stark contrast to how it was.” He mentions how there was no Taliban, not even the slightest vested Western interest in the country. They were a bunch of very proud people and one who took great pride in their ethnicity. The monarchy there then also gave the country its current shape and identity. “Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan were very open; you can’t even imagine that now,” he says with a shake of his head.

Ruedi shakes his head again as he tries to maneuver his Citreon on the busy streets of Delhi. “What the hell was that sound,” he asks his wife. They stop the car to look down. By the time their heads turn up, there is a huge crowd gathered around them, all of them looking at them wide-eyed as he nods in greeting to most of them.

One of them finally steps forward and asks,“Help chahiye babu?”

“Ah help! No thank you. We are okay,” says the blonde-haired man.

After not having spent too much time in Pakistan, they had decided to make the most of their time in India. So their first stop: Taj Mahal.

The majesty of this jewel of Agra has to be seen to be believed. It is white like it has been washed in milk. “Such extravagance!” Ruedi thought. Next came Banaras and they visited all the temples and ghats to take in the religious brilliance of the place. Sitting on one of the ghats, he looked at the Ganges flowing down under his feet and thought about the cultural difference that a place like Banaras had with an Islamabad. Such stark differences, when separated by only a small distance.

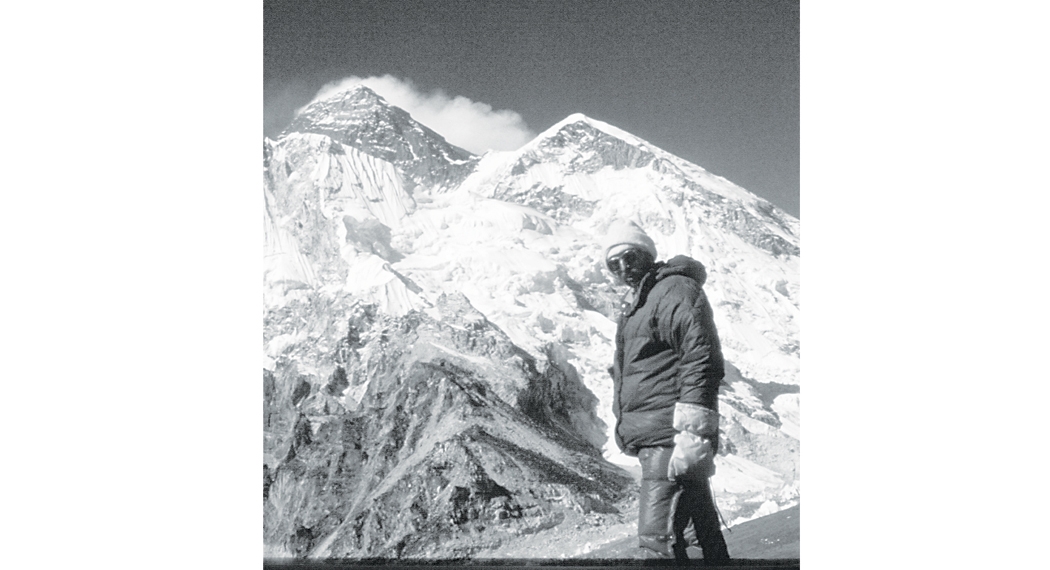

They arrived at the border and finally the Shangri-La of Asia awaited them on the other side. Ruedi had heard so much about Nepal that maybe he had blown it out of proportions in his head by now. At the same time, he had expected and heard of it being a quaint place full of simple people. The first sight was of Birgunj, and it was but a village. Nothing special, just a port of entrance as they went further up to a place that they had heard of called Daman. En route, on this highway called Tribhuwan, they had their first glimpse of the Himalayas. “Majestic,” she whispered alongside him.

“It was a great sight,” Ruedi reminisces today, “I was used to snow-capped mountains but seeing the Himalayas for first time was great, of course. It is one of the main reasons that we made the trip in the first place.” At the time, he says, Himalayas were a part of mythical folklore in the west and something that represented shamanistic ethereal entities that fascinated them. No wonder the hippies made their way here.

“It ‘s like a city, but it’s a village isn’t it?”he murmurs. The year is 1975, and the roads of Kathmandu are devoid of traffic. The Basantapur square is filled with foreigners and girls with flowers in their hair. He enquires about lodging and is astounded at the very economical rates. “Brilliant!” he says to himself and books some accommodation. And well deserved accommodation at that. They had spent almost two months sleeping in their car or their makeshift tent that they carried. It was about time they got themselves a 6 x 4 bed.

Ruedi soon contacts the friend he had met in the English language class back in Zurich, one who had pretty much lit the spark for his ‘across-the-world’ road trip. He said he lives in a place called Ekantakuna. No problem; they had a couple of bicycles at their disposal that they then pedaled to find him. The cycling adventure didn’t end there; Mr. and Mrs. Ruedi would cycle to Bhaktapur, Kirtipur, Boudha among many other places.

“Can you imagine all these places back then? They are so heavily populated now especially Boudha, but back then, there wasn’t even a hut on the way. Some farms yes, but clear blues skies and the road below. Forget pollution!” What a momentous time to be in Nepal surely. He also does give a unique insight into what was Thamel back in the 70s. “Just a dusty, dirty road,” he says. Well at least that’s come a long way.

A key moment at the time of his visit was on 24th February, 1975. The crown was passed on from King Mahendra to Prince Birendra in a grand coronation ceremony. But for some reason, all the foreigners were asked to leave Nepal during the time, mainly Kathmandu, where the coronation was set to take place. Ruedi tries to explain, “This was a security measure or even a religious measure I am not quite sure. But some people left and came back while some went to Pokhara.” He then adds cheekily, “Pokhara was a village of 1600 people by the way…”

“So this is the famous Fewa Lake?” Ruedi looks around to see the dried up remains of what was once a lake, or would become a lake he is not quite sure. Apparently, the dam was damaged and at this point in time in Pokhara, one could just walk to the temple that would only be accessible by boat and a paddle at other times. While all this had its charm, the man and wife had their eyes set on the peaks now. They checked the flight route and there was a flight to Syangboche, a little above Namche. Their pilot was a Swiss guy by the name of Ernst Wick and one who would point out the peaks to them high up in the air.

Syangboche was like a little haven. Upon arrival, Ruedi understood why some people would refer to these parts as the mythical grounds of Shangri-La. There was a certain fabled allure to it all. While walking along and speaking to the locals, one of them quite simply says to him, “We have a king in these parts too you know.”

“Sorry?” Ruedi excuses himself, certain he has not heard correctly.

“There is a king in Mustang sir.”

He is further told that the king is rather inaccessible to tourists but it’s within his kingdom that they are all residing.

His first trip to the lap of the Himalayas is something he can vividly remember to this day. “It was breathtaking and a great sight. The interaction with the locals was also a standout and you found out about so many unique nuances that are just so different from a place like Kathmandu or Pokhara.” The stand out bit of information was certainly about the King of Mustang and he laughingly says, “We had just been asked to leave because of one king back there!”

Their room in Kathmandu had the same warmth it always had but it was their last morning here. His travel route back was planned and they had decided to cross Afghanistan from the south and not from the middle, then the southern part of Iran and Turkey heading towards Europe. His year-long leave had been meticulously planned and he had already spent seven months out of them. As he looked out the window, the open Kathmandu road sprawled in front of him; he made a mental note to himself, “I’ll be back one day.”

And he did, he came fourteen more times, so much so that when you ask him about the difference between then and now, he answers like an old local. He talks about the price of basic foodstuff, a bottle of water, a liter of diesel or a loaf of bread.

Soon, he chose to organize treks across the country.

“Here is what we do. Our group comes to Kathmandu and we stay for three days in Thamel. Then we go to Bhaktapur, Patan and hike to Nagarkot. There we stay in Nagarkot, walk to Dhulikhel and stay there. We visit schools and hospitals in Dhulikhel, go to Barabise and visit the paper factory.” That is his plan; and the plan of Frank Adventure. It is all about getting a new insight into Nepal through the eyes of Ruedi Frank. It is about foreigners participating in weekly customs and family traditions of the people here. It is when you sit and talk to him that you truly feel his connection to Nepal. How he has earned his stripes to discuss the problems Nepalis face and how he is a good, credible voice to voice those concerns. He is, one of us for sure.

Ruedi is waiting for his flight in the summer of 1979. He has made detailed plans to spend the next three years working for the Swiss Government in Nepal. “Finally,” he sighs as the boarding Call beckons him to his plane. Settling down in his seat, he goes over the project that he is to be a part of in Sindhupalchowk; an integrated hill development project to be exact. He wonders, “Tourists should see all this as well, the development Nepal is making, the schools, the hospitals…”